Experimenting with Startup Studio Structures

How can we evolve our systems to marry productivity with self-actualization?

Introduction

Several posts ago I initiated what has become a loosely structured exploration of the nature of work in the Innovation Economy. It definitely wasn’t my intention! But with my thoughts so specifically focused on this weird area due to our IRL building efforts, there are many threads my brain feels compelled to pull.

I observed that even as compensation in the technology sector has risen to astronomical levels, there has persisted, or perhaps expanded, a robust feeling of unfulfillment. A key causal factor in this “achievement malaise” resides, I believe, in the structures of our work systems today; within the org charts and bureaucracies required to keep the modern corporation scaling.

To examine this “structural hypothesis”, we walked through a series of increasingly complex frameworks to establish a baseline of how corporations use structure (whether intentionally or not) to establish their competitive advantages as they scale. Economies of scale, scope, and variety are strategic levers employed by the corporation, but they also require specific structures that heavily govern how their employees must work.

And because most corporations have similar macro-structures, and thus similar macro-level restrictions on how their employees should work, it should not be surprising that a not-insignificant portion of our brightest innovative minds would exhibit scaled unfulfillment – their personal needs are misaligned with these corporate structural imperatives. We thus turned to the startup ecosystem once again to explore whether a great proliferation of startups might provide at least a minor salve1.

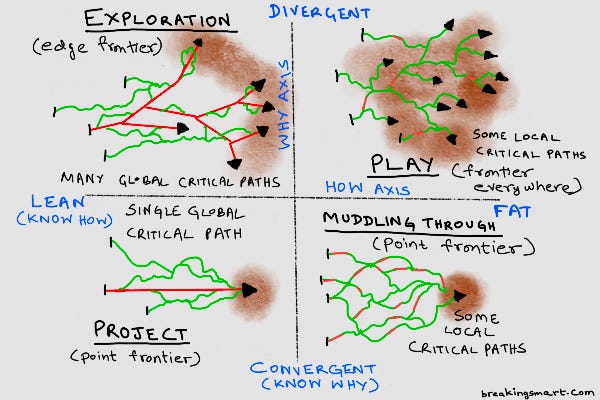

Tl;dr, I’m a bit skeptical - not because startups don’t provide tremendous value, both to society and to individuals, but because the structures of startups do not themselves appear to resolve any of the tensions we’re looking to relieve. Startups offer more autonomy for sure, but structurally they are not nearly as dissimilar from the corporation as one might think. I’m thinking here once again about the GUTS framework:

More specifically that most companies, or at least most individual work, exists purely within the confines of one quadrant, especially on the left side – LEAN work – which is focused on efficiency, not on creativity (which lean corporations must see as “waste”). We require much more extensive innovation in our structures of work, and at the end of that piece, I offered that startup studios offer, well – they at least offer something different, even if presently insufficient for our means.

And so we’ll take that up here - further exploring how the startup studio provides an interesting foundation for further innovation around the structure of work itself. I’m ultimately interested in exploring how to create a for-profit environment that enables the most talented people - at any life stage - to be their most creative selves. To combine capitalism with self-actualization. To remove as bureaucracy as possible to just build and get shit done.

Building Diversified Work

In Well Fed and Unsatisfied, I posited that there are four primary vectors for one’s work structure:

Time Allocation: Persistent vs. Idiosyncratic

Compensation: Fixed vs. Participatory

Portfolio Type: Concentrated vs. Diversified

Organizational Size: Small vs. Large

And within this framework, the majority of corporate jobs today are Persistent and Concentrated. Let’s focus on this latter point for a moment. I’ve discussed the concept of the “diversified work portfolio” and its relationship to personal fulfillment – that greater variance in one’s work is likely to increase levels of fulfillment (and probably productivity) for a significantly large proportion of total knowledge workers. This is simply not possible within a traditional corporate structure, especially as a corporation scales. Roles become narrower and narrower, and there are relatively few teams within companies who are structurally set up to work across a variety of domains.

Startups target generalists at their earliest stages because there’s so much work to be done across multiple domains; startups do, in fact, encourage greater work diversity than corporations. But that work is still focused on a singular product.

Startup studios offer an interesting counterpoint to the traditional startup in this specific regard. Not only does the work vary, but the products themselves vary. That is, startup studios are specifically structured to create diversified work portfolios, and as we discussed in Foundational Frameworks for Strategic Growth, this diversification flows out of the Startup Studio’s focus on Economies of Variety, which is much more closely aligned to the human condition itself:

“Hominids, effectively, were selected for having brains capable of generating and adapting to variety in software rather than hardware. We are not only more exploratory and curious than most species, we have hardware that can handle a lot more variety and survive. So companies that figure out economies of variety are to industrial age companies as hominids are to other animals: they’ve grown an organ analogous to a brain through a process like variability selection.”

Put differently, humans are evolutionarily focused on diversity and variety. To increase efficiencies, corporations choose (rightly) to strip out this variance and effectively treat each person more cog-like as the corporation scales2. Thus, corporate scaling necessarily drives (many of) its employees further and further from their “organic state”, and it is here that unfulfillment arises for so many.

Success has been earned through focus and a stripping away of “ancillary” interests in order to achieve, both for one’s self and for the corporation. But once achieved, that person is effectively stuck - pigeonholed by her own success. We see this prominently within the ranks of academia, where researchers are forced into tinier and tinier niches in order to own a novel scholarship sector, and yet we’re surprised when 80% of leading researchers would choose to work on different projects if given the opportunity.

In summary: one thing that intrigues/excites me about the startup studio structure is that it is explicitly designed to enable work diversification by focusing on Economies of Variety, and as I’ve written, variety can often be leveraged to build Economies of Scope.

Economies of Scope

Thus far we’ve discussed the variety that startup studios provide their employees - a freedom to work on multiple projects in parallel, forever. Let’s call this “parallelized variety”, due to the temporal simultaneity of the work. But there is a second piece of variety that flows directly from the great volume/diversity of companies outputted by a Studio.

Let’s take two HoldCo’s in very different industries: Union Square Hospitality Group (USHG), one of the leaders in dining/hospitality, and Constellation Software, the leading consolidator of vertical software businesses. Very different industries with very different business models, and yet they both leverage their portfolios to offer diversified work to their employees.

This is not parallelized variety, however – one of their employees is (typically) dedicated to one company at a time. No, the variety they enjoy comes at a different time scale, typically in years - when one feels like she has hit a wall and needs a new challenge. For most companies, the solution here is, most often, to lose the employee – the new opportunity she is seeking is simply not available at the current company, who by design do not offer variety.

USHG and Constellation are not normal companies. They are HoldCo’s, and all HoldCo’s have a portfolio of companies. That is, they offer a wide variety of employment opportunities for nearly every employee. If one feels like she’s hit a wall, or simply needs a change, each HoldCo is significantly more likely to retain that employee by offering a shift to a sister company within the portfolio.

Kevin Kwok calls this the “farm club model of talent retention”, which he coined while specifically exploring USHG:

“USHG is a constellation of very different restaurants and chains. Unlike many restaurant groups, this variety means Union Square Hospitality Group can hire people early in their careers–and plan for them to advance their careers from within USHG. You can start working at Shake Shack, and then move on to managing their own Shake Shack or working in one of USHG’s more upscale restaurants. This is true both on the business or chef sides of the business. If you do well you could go on to run a restaurant in USHG’s portfolio. Or if you wanted to open your own restaurant, you could open one with Danny Meyer as part of USHG–or start your own restaurant and have USHG as an early investor.”

Let’s call this type of variety “sequenced variety”, to distinguish its temporal distinction from parallelized variety. Taken together:

Parallelized variety offers employees diversity of work within the same time period and flows out of businesses structured to capture value from Economies of Variety.

Sequenced variety offers employees diversity of work one after another and flows out of value captured from Economies of Scope.

Note that parallelized and sequenced varieties are orthogonal – hypothetically a company can offer both, but typically it’s one or the other (or neither). There’s one inconsistency in what I’ve offered here, however…

HoldCo versus Sellers

Companies can only offer sequenced variety within a holding company structure, as there must be a perpetually-held portfolio available. This structure almost without exception arises from more traditional private equity-funded M&A activity rather than organic growth.

Startup Studios, as presently constructed, are almost without exception focused on building valuation businesses - startups that take on venture capital and will be run unprofitably for years before being sold off. Liquidity comes in the form of exits, which by definition means that these companies are not held by the studio in perpetuity. Startup Studios are not HoldCo’s.

There is an alternative here that I’m most keenly interested in exploring. What would it look like for a Startup Studio to be a HoldCo? Well, it would take a different type of business entirely. Rather than building valuation businesses, this studio would need to build cash flow businesses. These businesses would be held in perpetuity just like a traditional HoldCo, but would be built organically, rather than via acquisitions. This is the first major variant on the Startup Studio structure we’ll explore in future newsletter posts (and that I’m actively building within our company.

Centralized vs Distributed

Another central tenet of the Startup Studio is its centralized structure. All ideation, research, and initial prototyping is carried out within the studio, and only after some traction is established does the Studio (typically) recruit a CEO/President/GM to solidify, spin out, and scale that business, at which point the Studio has no more active engagement with the company.

The centralized nature of the structure offers great parallelized variety at a relatively low cost, both of which are great features! The downside, of course, is one of capacity – there are only so many projects on which a person can be reasonably productive in parallel. And thus, this capacity issue manifests as a scaling issue - without significantly increasing internal headcount at the studio, annual outputs per studio have historically been capped at around 3-5 companies per year.

Innovation scholar Sam Arbesman wrote a piece back in 2012 called “The Rise of Fractional Scholarship”. The concept is similar to SETI@home, swapping out distributed computing for excess cognitive capacity. I think there is potentially an opportunity to adopt this principle within the studio, effectively aggregating fractional productivity to construct a distributed studio. Rather than studio members building in a silo, the work in many/all phases is instead distributed across a network of contributors.

Difficulties abound:

Talent Acquisition. We’re now moving from a small studio of less than 20 members to potentially needing to recruit (whether passively or actively) hundreds or thousands.

Coordination. Keeping a single project with a dedicated team on track is difficult enough. Keeping dozens of concurrent projects with scores of disparate workers is exponentially more complex.

IP protection. With so many fractional workers (i.e., non-employees), how does one ensure that all of the proprietary information is properly protected?

Compensation. How does a studio afford to pay such a large volume of fractional workers when so much of what they’re working on is expected to fail (by design)?

There’s far more complexity here than a pithy set of bullet points can properly communicate, and I’ll definitely be writing about this further. But conceptually this is incredibly appealing! Not just because of the potential scaling impacts, but on the broader impact it may have in offering a much larger swath of knowledge workers a new paradigm for building a diversified work portfolio – and a persistent one at that.

A concluding reminder that the modern corporation has functionally only existed for a century, and the startup studio for a quarter of that. We’re in the very early innings of experimenting with different structures that may yield positive returns both for productivity and for individual fulfillment. Let’s get building.

Hypothetically of course. The fundraising market is relatively tough even now!

I didn't initially make the connection, but this feels eerily similar to "Seeing Like a State"