Cracking the Glass Ceiling

An attempt to break down structural gender biases to improve our innovation capacity.

Introduction

I’ve spent the past couple of weeks diving into the insidious and unfortunate gendering of our venture capital (innovation) funding.

In “Gender Inequity of Venture Funding”, I unpacked the stark truth about venture funding for women today. Nothing groundbreaking here but necessary for establishing the foundation for how we start to solve for it.

In “Venture Capital and Structural Bias”, I waded into more uncertain waters in an attempt to understand why venture funding is so unacceptably poor for female founding teams.

For the more left-leaning readers, this represents yet another manifestation of our patriarchal society. Though I’m certainly sympathetic which such politically-tinged arguments, I’m attempting here to reframe the argument slightly into one of maximizing human progress.

As I’ve written previously, human progress emerges from our efforts to grow, and those efforts are powered by innovation. If one agrees with this logic train, it is absolutely vital to our species (regardless of your place on the political spectrum) to support any efforts that allow us as humans to maximize our global capacity for innovation.

And perhaps the largest area of opportunity (the unfortunate other side of the bias coin) for accomplishing this goal lies with women; and more specifically, closing the gap in innovation funding not by denigrating male founders but by elevating female founders to the current levels of their male counterparts.

So in this final piece in the initial troika exploring gender inequity in venture funding, I’ll offer some potential solutions for this funding atrocity; to chart a path toward gender equity attempting to “incubate” founders that, when successful, will help us secure that 15% GDP bump.

Founder incubation is a very niche piece of the venture industry today. Companies like Entrepreneur First in the UK explicitly exist to “select the world’s most talented people to join our cohorts, find their ideal co-founder, and build from the ground up”. Their raison d’être is not to find and fund founders but to create them.

This is indisputably a great service to the Innovation Economy, but the level of founder enablement we require is orders of magnitude higher than any given incubator can consider on its own. Said differently, the problem at hand is unfortunately not “cohort-sized” - we’re not talking about tens but tens of thousands of new founders here.

There are no simple fixes, all of this work is difficult, but if we truly wish to increase US productivity and growth, we must willfully swallow “difficult” and get to work.

Let’s dive in and make things a bit uncomfortable.

Near-Term Fixes

The first class of changes we’ll discuss here is of the near-ish term variety. If we assume the present demographic orientation of the market, what can we do to build an environment far more conducive to female founders? I would offer three different mechanisms:

Expanding funding applications

Interview interventions

Actually penalizing sexism

Expanding Funding Applications

Venture funding today is primarily an exercise of social networking. As I covered last week, investors very often fund the best networked, not necessarily the best ideas or best operators. Such a broad dependence on existing social networks and on face-to-face meetings both disadvantages the under-networked (women and especially people of color) and very likely drives poorer investment outcomes.

Adoption of online (cold) applications for funding is an obvious, necessary, and immediately implementable tactic. Applications yield two primary counters to the networking biases of the present system:

Broadening the founder pool by granting access to a much wider swath of investors.

Limiting (but not eliminating) gender biases present in the initial evaluation of a given pitch.

The largest public funding programs like the NIH have always made their funding decisions based first on standardized application processes. The Gates Foundation similarly makes investments using double-blind applications, and has gone further to study the impacts of such procedures, finding that applications significantly limit gender biases but don’t completely eliminate given the differences in communication styles between male and female submitters (with males using broader language that is more appealing to most evaluators).

Venture is slowly creeping in this direction. Kapor Capital shifted to an online application process to ensure that they can reach the best ideas, not simply the best networked ideas. More recently, an incredible group of (mostly) individual pre-seed or seed investors mutually assembled to form Seed Checks, enabling anyone to pitch without any warm introductions necessary.

But we need to supercharge these efforts. Applications don’t require the elimination of meetings, and plenty of deals will still originate through social networks. It is inarguable that there is valuable information captured within these networks that isn’t captured within an application. But if we want to attract all potential talent, and fund the best possible ideas, maintenance of the status quo - social network-driven funding - is simply insufficient.

Improving In-Meeting Biases

If we assume that applications become more normative and widespread, but also acknowledge that in-person pitches will persist indefinitely, we also need to make some changes to how such pitches are conducted. A quick reminder of the challenges we’re trying to overcome:

Humans favor “maleness” (physical attractiveness, voice pitch & timbre)

Male investors challenge the bona fides of female founders more strongly than male founders.

Male investors focus more heavily on risk aversion than upside opportunity with female founders.

Later in the piece we’ll discuss the obvious but longer-term salve here - simply tilting the investor balance from 10% female will counteract some of these male-driven biases. But as the task here is to improve conditions given the current demographic distributions, what opportunities do we have?

We can glean some learnings from the symphony, which, like venture, has exhibited significant gender inequity. In response to the numerous lawsuits that arose in the 1970s-1980s, American symphonies started using an “innovative” solution:

Yes, we’re taking here about blind auditions. Researchers found that by adopting such tactics, female musicians were 50% more likely to make it through preliminary rounds. Though the researchers acknowledge the large error bars of the study (not least of which because of the small n problem of studying symphonies), most symphonies today do in fact utilize blind auditions, and female participation has increased from under 6% in 1970 to ~40% today (with gender parity in the New York Philharmonic).

I make this analogy not because it’s perfectly applicable to our venture situation - the voice is very obviously not masked by a screen - but to illustrate that interventions intent on limiting gender bias can in fact drive significant changes.

Perhaps the initial online application effectively “inoculates” against some of the bias by putting the idea ahead of the person, but I’m also reminded of something Sequoia’s Roelof Botha noted in “The Power Law” - that he was gravely concerned the firm’s investing decisions were not actually consistent; that a yes today may turn to a no the following Monday, simply because the context in the investment meeting naturally shifts week-to-week.

I think the principle might also apply here. Firms likely could benefit from training/interventions focused specifically on the clarity of their decision-making, perhaps building structured counterfactuals into the process, such as:

“If we heard this same pitch from xyz male founder we already funded, would we feel differently about this idea? If so, why”?

In theory, such interventions could help retrain investors to adjust their credentialing or risk/opportunity biases, and hold them accountable to persisting these “gender adjustments” for the longer-term.

I’ll admit, though, that I’m a bit more skeptical of such interventions in practice. Everyone says they read Kahneman or Annie Duke, but relatively few in my experience actually put any of these learnings into practice. Skepticism aside, we absolutely must find ways to improve such widespread gender biases, and investors themselves should also want to given the potential alpha such interventions may yield.

Penalizing Sexism

Quite obviously, sexism of the overt variety - gender bigotry - cannot be tolerated. There are no simple fixes here. Culture of the firm matters, and thus leadership as well. Often these behaviors start at the top, which makes excising that much more difficult.

The only real remedy here is consequences. Without meaningful consequences, perpetrators are more than happy to continue perpetrating once the firm’s attention shifts. I’m talking here about major fines, demotions, or expulsions.

But these are the more black-and-white cases, whereas so much of what we’ve discussed across the past 2.5 pieces is sexism of the implicit, if systemic, variety. This form is much more difficult to mitigate because of the (often) gray area in which this conduct resides.

It’s an area that requires modification of the casual sexism of our culture writ large, which is unfortunately not something that can be solved within the venture ecosystem in isolation. And I’ll admit that, as a white male operating within this broader culture, I don’t feel equipped to solve for it, precisely because I don’t easily notice and/or experience it. We must be better.

Longer-Term Fixes

The next class of changes we’ll discuss are far more challenging as they require us to fundamentally shift the demographic makeup of the Innovation Economy. We have three parallel paths to alter here:

Tilting investor composition

Creating more female founders

Closing educational gaps

Tilting Investor Composition

It bears repeating once again that 90% of venture investors are male. There is simply no way to achieve funding equity when the funder composition itself is so heavily gendered. An increasing number of (male) venture investors were once founders themselves, and thus we should expect that by growing the female founder pool over time, the total number of female venture investors will also organically rise.

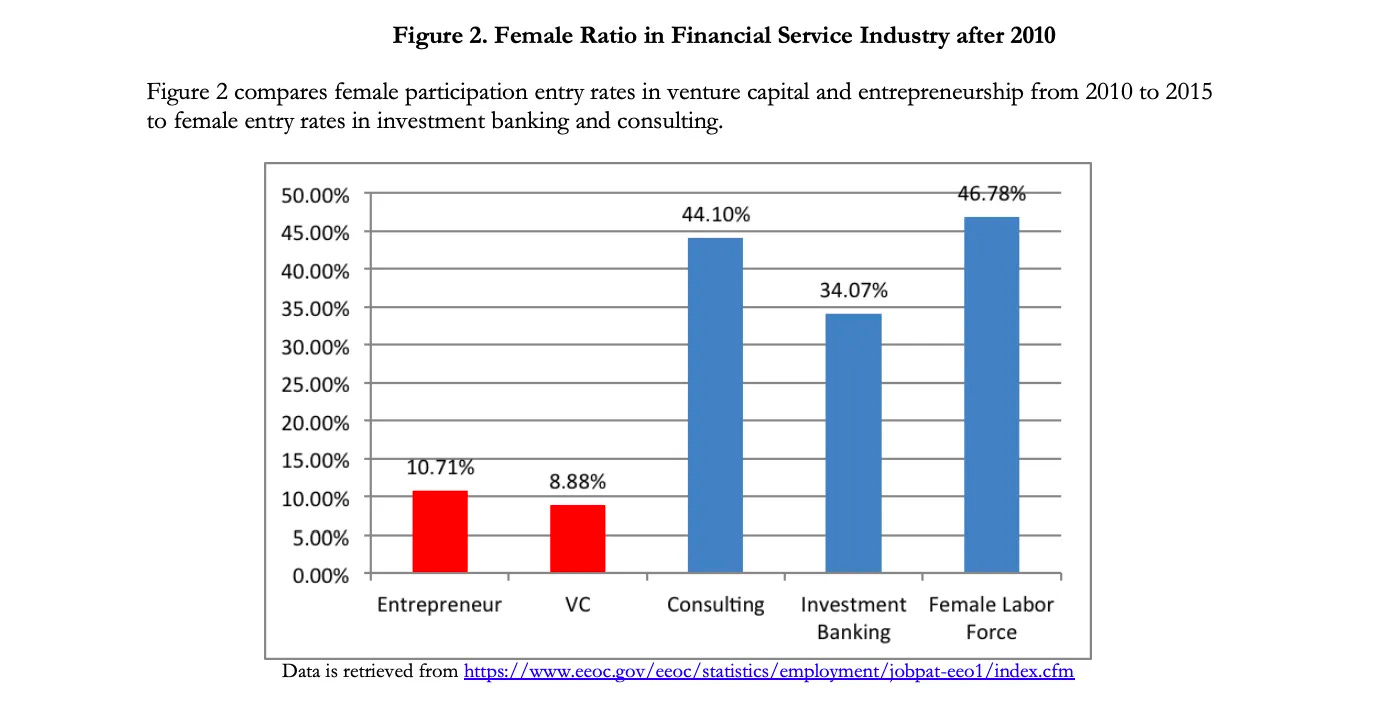

But if we wanted to kickstart female investor growth, we’ll have to pull from a different talent pool - perhaps from the Investment Banking and/or Management Consulting sectors we discussed previously?

It’s certainly easy to look at such a chart and quip “all we have to do is redistribute some talent from another industry”, but how? How might we systematically compel dozens or hundreds to shift their investment focus en masse?

The most obvious point of leverage here is a standard hiring incentive - promotions. The major venture firms could acquire top younger female consulting/banking talent as partners earlier than they otherwise would/could have achieved in their current company.

Perhaps this is enough to substantially close the investor gap. We simply don’t need nearly as many funders as we do founders to structurally alter the gender gaps here. That said, I’ll admit I struggle with what other structural incentives might drive macro-level changes - I’m curious if you have any further ideas here.

Creating More Founders

I’ve already discussed the sizable pools of talent currently tucked into other industries (management consulting and investment banking in particular) that could easily be leveraged to create more investors, and potentially this pool could be leveraged for founders as well (though the venn diagram of talents is far less overlapping here).

But I believe that we can turn to another pool of talent that already resides within the industry; one that has grown wealthy yet unfulfilled; stable yet restless; one that the industry shed in record numbers the past couple years as it woke up to the realization that it could do just as much if not more, with less.

I’m speaking of course about the tens or hundreds of thousands of seasoned operators, thinkers, and builders currently collecting paychecks from the mega-corporations of tech - your Apples, Amazons, and Microsofts.

The mass layoffs I flippantly just referenced have dominated the tech news cycle in recent months, and rightly so, but the fact still remains that tech behemoths still employ whole cities worth of our best and brightest.

Compelling such a talent pool is, as one might suspect, challenging - this group is paid incredibly well, but sadly not well enough to leave and start a company without significantly harming her, and more importantly her family’s, financial position. Ramen dinners may work for new grads who haven’t yet built lifestyles requiring well-earned and healthy pay, but this model is a non-starter for most professionals, especially those raising children.

Must we concede that the only people we want as founders are those willing to forego livelihood for (potential) fulfillment? My bias here is obvious - I think the “ramen founder” concept is completely fucking nuts and unacceptable, a fetishization of “poverty for the sake of innovation/ambition” promulgated by the wealthy (investor) class.

Let me be clear that I’m not suggesting that sacrifices shouldn’t be made - it’s simply inconceivable for a founder to maintain the $300k+ base salary - but if we truly want to better leverage our most talented for progress rather than (intellectually) wasting away at the Google or Meta country club, we require different systems that innovate the funding of innovation.

Yes, I’m ultimately talking about reforming and evolving venture capital and our other innovation funding institutions, which is not a simple or short endeavor! I’ll provide some base ideas here that will require further unpacking in future posts:

Risk-Adjusted Investments

A highly skilled female engineer with 2 kids earns, say, $400k/year at Google, and though she likes her colleagues and (obviously) enjoys the fruits of this compensation, her work simply doesn’t matter. She’s unfulfilled and wants to build her own thing.

Leaving her job to start this idea is simply not feasible, and even once the product is fundable, she simply cannot accept a salary lower than $250k, far greater than what most investors would allow. Have we reached an impasse?

A typical first funding round for a new startup will typically sell off 20-30% of the company, with (in most cases) an expected founder salary cap of ~$150k. So we’re effectively talking about a $100k delta in investment utilization - what should that be worth to the investor? Another 10% ownership stake? 20%? Surely there’s a number in there that makes sense if the investor truly believes in the founder and knows the alternative is she won’t actually be a founder.

Switching to the opposing party - Is the founder willing to take on this massive dilution in order to roughly maintain her lifestyle while building the thing she actually wants to? I can’t be sure, but I know that the system as currently constructed does not properly incentivize what are in many cases our best talent (skills plus operational experience).

Mid-Career Grants

What if we take this idea one step further. As an investor I know that there are n female senior project leads at Microsoft that could create incredible value if they were “spun out” of the mothership. Mind you they don’t yet have that killer idea, but you’re mutually convinced that, given the time afforded by the absence of a full-time job, she can get there.

If you as the investor were to offer $100k-$150k for a 6-month sabbatical, would she accept it? Would I make that deal?

I’m not totally sure if I would do so with zero strings attached, but I might! And ultimately this grant-making endeavor could, in theory, yield substantial value in spite of the risk.

Grants are more appealing (and affordable) for those less attuned to 1% salaries (e.g., early career, academics, etc). The Thiel Fellowship and Emerging Ventures have already utilized them to attract fantastic talent, but they are typically targeted to younger recipients (especially in the case of Thiel) or are lower value “financial nudges”, and in both cases at relatively low volume.

What would it look like to build a scaled grant-making program within industry to incentivize thousands of our best (women) to build new things?

Startup Studios

What if we also proliferate and expand the startup/venture studio landscape? You can read the bible on this, and

writes a Substack explicitly geared toward tracking them. The concept is relatively simple - a studio is a cross-functional group of seasoned operators that manage the design, prototyping, and launching of new startup concepts, most of which don’t work. But when they find a hit, they spin the product out of the studio into a standalone company and hire a CEO to run the company in a more traditional manner.There are tradeoffs with everything, and in this case, the substantial de-risking underwritten by the studio must be paid for by a heavy slice of equity - the majority in most cases. For many entrepreneurs this is a non-starter, and understandably so, but for the cohort that we’ve been discussing here - those who simply can’t take a pay cut to zero to launch a new venture - this tradeoff may be far more appealing.

Closing Educational Gaps

A final piece of our longer-term plan to close the gender gap starts much earlier, so that we build a more stable foundation of female technical talent for future generations. As I wrote last week, women now represent more than half of STEM jobs but not in the information technology domain:

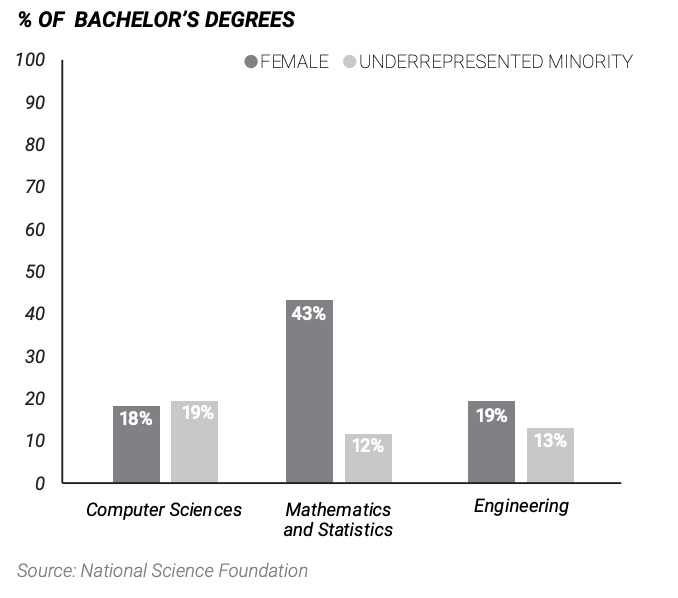

And this joint computer science + engineering deficit expectedly represents education deficits in which women still represent just 20-22% of undergrads in the US. This was not always the case! From Mar Hicks’ “Programming Inequality”:

“women were the largest trained technical workforce of the computing industry during the second world war and through to the mid-sixties”

From The Guardian:

“But by the 1970s, there was a change in mindset and women were no longer welcome in the workplace: the government and industry had grown wise to just how powerful computers were and wanted to integrate their use at a management level. “But they weren’t going to put women workers – seen as low level drones – in charge of computers,” explains Hicks. Women were systematically phased out and replaced by men who were paid more and had better job titles.”

But by 1970,

“women only accounted for 13.6% of bachelor's in computer science graduates. In 1984 that number rose to 37%, but it has since declined to 18% -- around the same time personal computers started showing up in homes.”

We do actually see near gender parity within the mathematics and statistics degrees. Given the similarity in intellectual and technical commonalities with engineering and computer science, the latter deficits are all the more damning and curious.

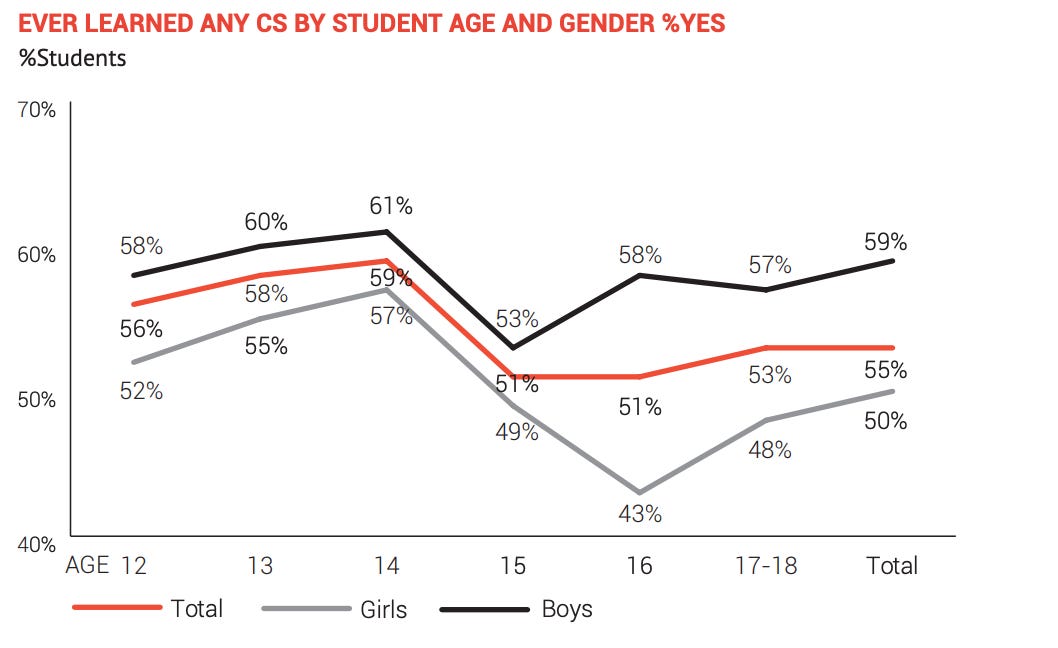

The question we’re asking here is not whether the gap will close, but how we can accelerate the closure. Google partnered with Gallup to research the education gaps in question, tracing the undergraduate inequities back further to secondary education:

Until the age of 15, males and females demonstrate rough equality of computer science training, but by 16 the gender gap expands and never fully recovers. This behavior stems not from differences in perceptions of the value of computer science but from differences in perceptions of one’s own abilities.

“While girls, overall, feel they are as or more skilled than boys in English, music, searching the internet and working with others, girls are much less likely than boys to:

Feel they are skilled in STEM classes like math (37% of girls vs. 48% of boys) or science (33% girls vs. 48% boys)

Be very confident they could learn CS if they wanted to (48% girls vs. 65% boys)

Say they are very likely to have a job someday where they need to know CS (22% of girls vs. 35% of boys)”

Much of the above is school mandated-learning, which is the primary reason why the gender gaps are smaller than one might expect. If we instead turn to self-interest, a very different (dismal) picture emerges:

I don’t think it’s a coincidence that gender deviation in CompSci interests begins at puberty - the period in which anatomical differences start to exacerbate gender differences but also when social conformity kicks into high gear.

At this point one may conclude that the divergence of interests at puberty illustrate innate biological differences, and we of course have male engineers writing manifestos proclaiming that women are genetically inferior at coding.

Let me be clear that such gender differences in computer science are social constructs, manifested by gender conformist reinforcement, not by innate gender differences in ability. I don’t say this flippantly - research bears this out.

From a separate Google study:

“dominant groups are less likely to think there are extrinsic or structural barriers and more likely to think there are intrinsic barriers for girls and underrepresented minorities”

As expected, both male teachers and male parents are more likely to ascribe intrinsic factors (e.g., lack of interest, lack of skill) to a female student’s/child’s drop-off in computer science participation relative to the extrinsic factors that play a massive role.

“Boys are much more likely than girls to have been told by teachers they would be good at CS (39% vs. 26%). The gap is even wider for encouragement from parents, with 46% of boys having been told by a parent they would be good at CS compared with just 27% of girls.”

The remedy here is both obvious and obviously disconcerting, given how poorly it has been implemented, again from the Google & Gallup survey:

“Parents and teachers telling students they would be good in CS has the largest effect on students’ interest in learning CS of any metric used in the survey”:

“Students who were told they would be good at CS by a parent are more than three times as likely to be interested in learning CS in the future (49% vs. 13%). A teacher’s perspective also plays a critical role in encouraging student interest in learning CS.

Students told by teachers they would be good at CS are 2.5 times more likely to be interested in learning CS (43% vs. 17%).”

Such positive reinforcement of computer science skill has numerous adjacent, second-order benefits:

“Have learned CS (69% encouraged vs. 46% non-encouraged students)

Have learned CS online (50% encouraged vs. 28% non-encouraged students), in a formal group outside of school (29% vs. 15%), or in a group or club at school (34% vs. 19%)

Say they are very skilled in math (49% encouraged vs. 39% non-encouraged students), science (49% vs. 36%) and searching the internet (77% vs. 58%)”

What’s most striking about these findings is that this encouragement has a negligible effect on participation in other areas like English, music, or sports. Put differently:

Math and science are areas of specific socially-engineered gendering that reverse when female teens receive positive reinforcement about their abilities.

And these gaps even affect those female teens who have actually expressed interest in computer science!

“Girls who are very interested in learning CS in the future are less likely than CSinterested boys to have been told by a parent (54% vs. 72%) that they would be good in CS. And even girls who feel they are very skilled in math (33%) and science (30%) are less likely than their counterpart boys (49% and 53%, respectively) to have been told they would be good in CS.”

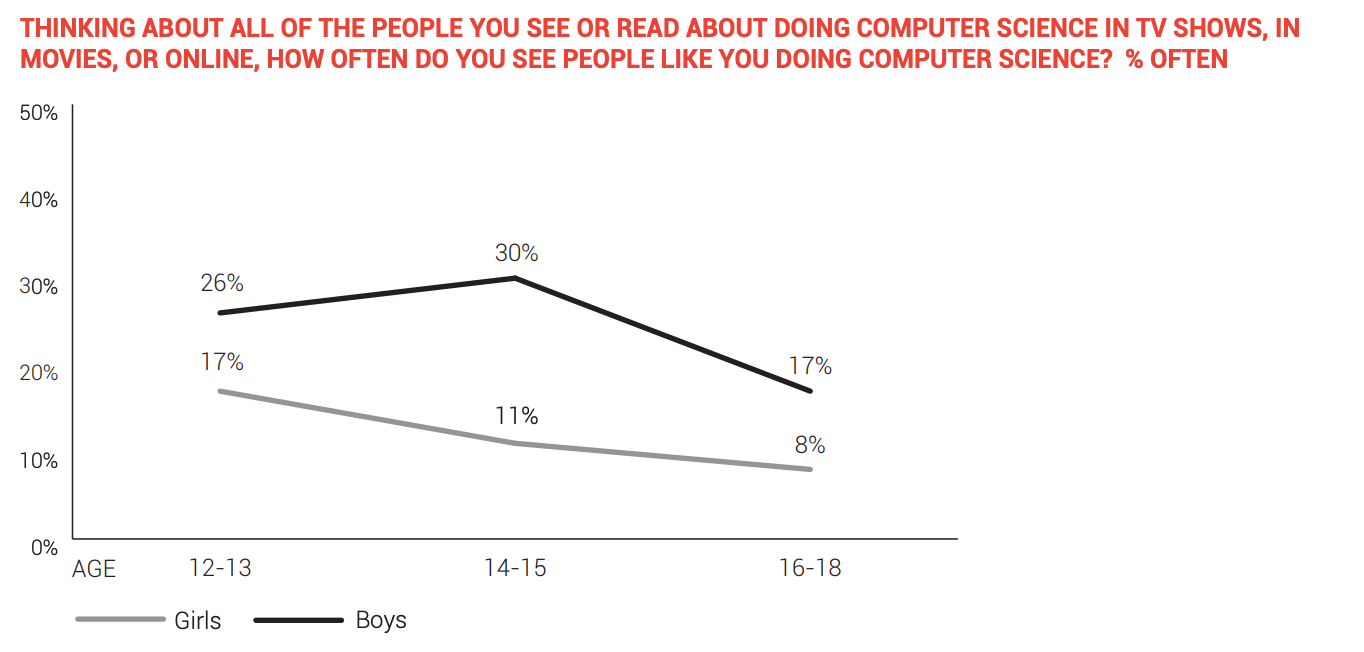

The effect here is not just from positive reinforcement, though this is the most potent. Instead, there’s also significant gendering in role models within computer science:

Google’s study of Unconscious Bias in the Classroom lays out the underlying theoretical challenge at play here:

“The insidiousness of unconscious bias (UB) is that it can lead to self-fulfilling prophecies that create and perpetuate inequities between groups, even when there was no preexisting difference in ability and the UB (stereotype) was, by definition, incorrect.”

There is a robust literature1 across social psychology, neuroscience, sociology, and economics that describes the various mechanisms of bias in play here. I won’t cover them all here, but an important point is that:

“humans are not born with an innate UB towards a particular group, but rather are exposed to a series of environments and experiences, which are both consciously and unconsciously stored in our brains, and later influence our instantaneous, automatic decisions”

The obvious challenge with this type of work is how subtle, persistent, and consistent the contextual and behavioral changes are. Whether manifested by parent or teacher, unconscious biases are not easily identified! Studies have shown mixed returns from interventions - with the most favorable typically occurring in smaller class sizes, which unfortunately does not reflect the nature of most classrooms.

But should we invest heavily to improve such conditions for young girls? Of course! And though such funding most often comes directly from public funding (whether governmental or non-profit), this feels like a great avenue for private<>public partnerships, not least of which because it is the private sector that will be most responsible for employing these students the decade after such interventions are enacted.

Conclusions

Human progress requires innovation, and to meet the needs of a growing population with multi-planetary aspirations, we need more innovators. There is simply no world in which 2% of venture funding to female founders, or more charitably a quarter to mixed gender teams, represents the optimal state of venture (innovation) funding.

Yes, investors today are at least partially correct when they proclaim that they can only invest in what they see, and it is indisputable fact that only a quarter of founders today are female.

The gross error is stopping there. Venture alone invests $100B+ annually into the American innovation ecosystem, and yet there appears to be no will, let alone capital, to attempt to close the gap by (financially) enticing more hyper-talented women to found companies.

This is, I think, a coordination problem exacerbated by willful ignorance. Venture today is highly fragmented, with no single firm capturing even 10% of capital deployed, and under such conditions it is often difficult to coordinate industry-level behaviors2. This work is difficult and not immediately value accretive, though with more of the mega-firms shifting to evergreen funds, the time horizons with this work are converging.

It’s about time we as an industry moved beyond “equity via press release” and instead toward the actual building of systems that accelerate equitable investment.

This article does a great job covering the various literatures in brief.

Unless of course the behavior is catalyzing a bank run.