Introduction

One of the initial ideas we’re exploring within our nascent venture studio is in the charitable giving “industry”. Given the largely not-for-profit nature of donations, most do not consider this an industry at all, let alone one that should ever garner the gaze of a capitalist. I get it — there’s something inherently distasteful about the prospect of profiting from nonprofits — and having worked in this for-profit<>nonprofit space for several years, I’ve witnessed firsthand both ends of the spectrum. But as you’ll see shortly, nonprofits hang persistently on the precipice of insolvency, and better, more consistent, more scalable solutions are required to ensure not only that nonprofits can continue their necessary work but optimally expand it far further.

Charitable Giving is Huge

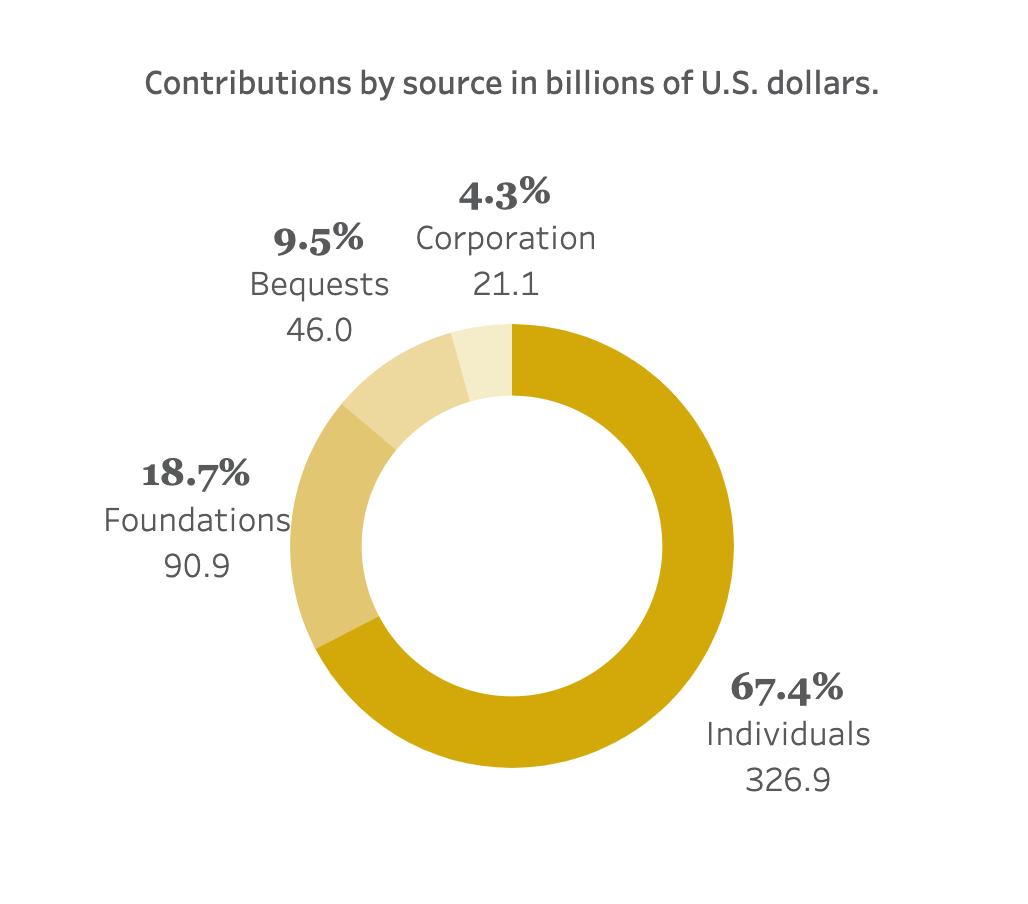

Charitable giving in the US is a massive annual capital exchange, with total 2021 giving reaching $485B. Approximately two-thirds of these donations come from individuals each year:

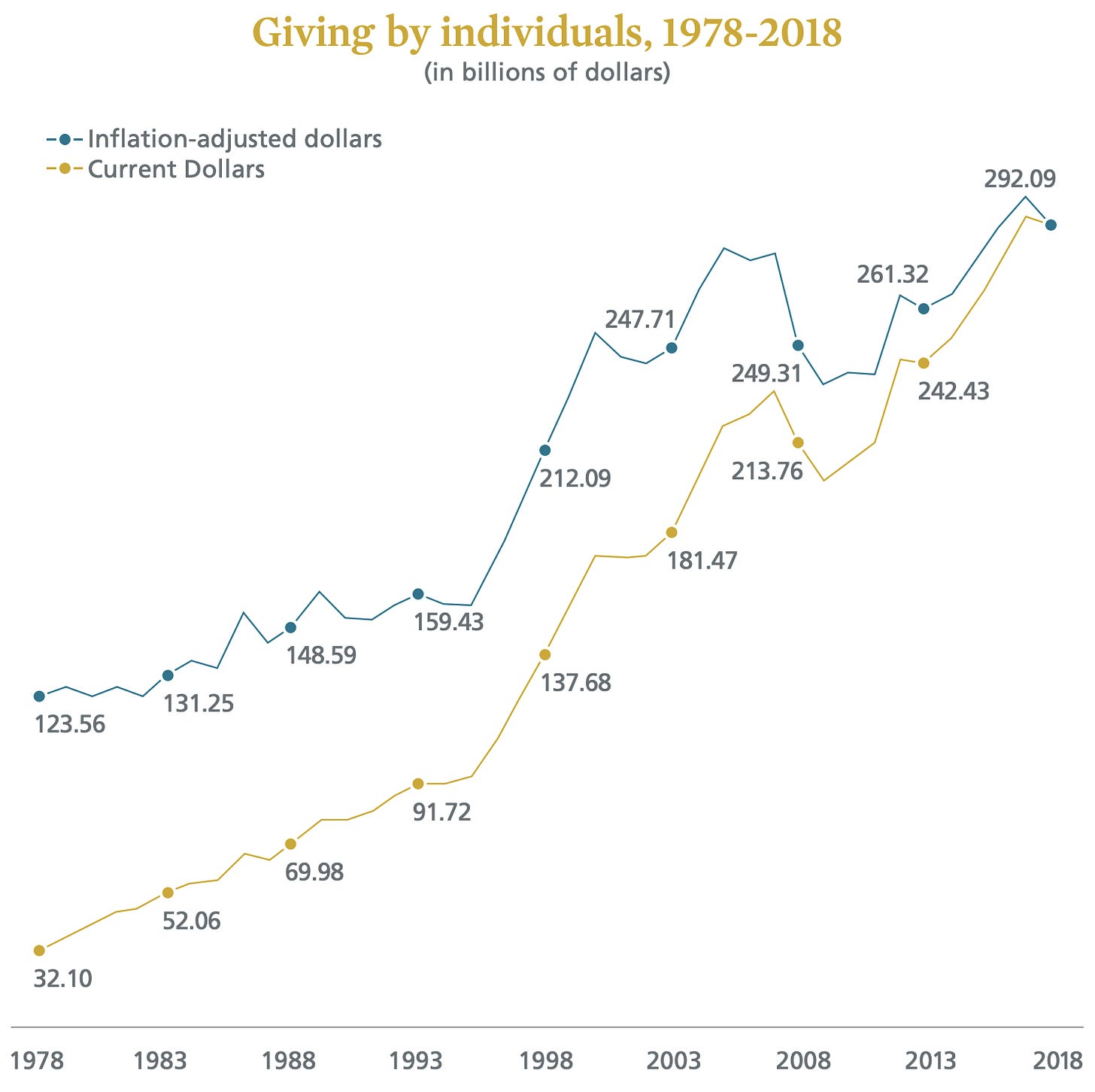

And donations from individuals have grown at an inflation-adjusted 2.2% CAGR over the last 40 years:

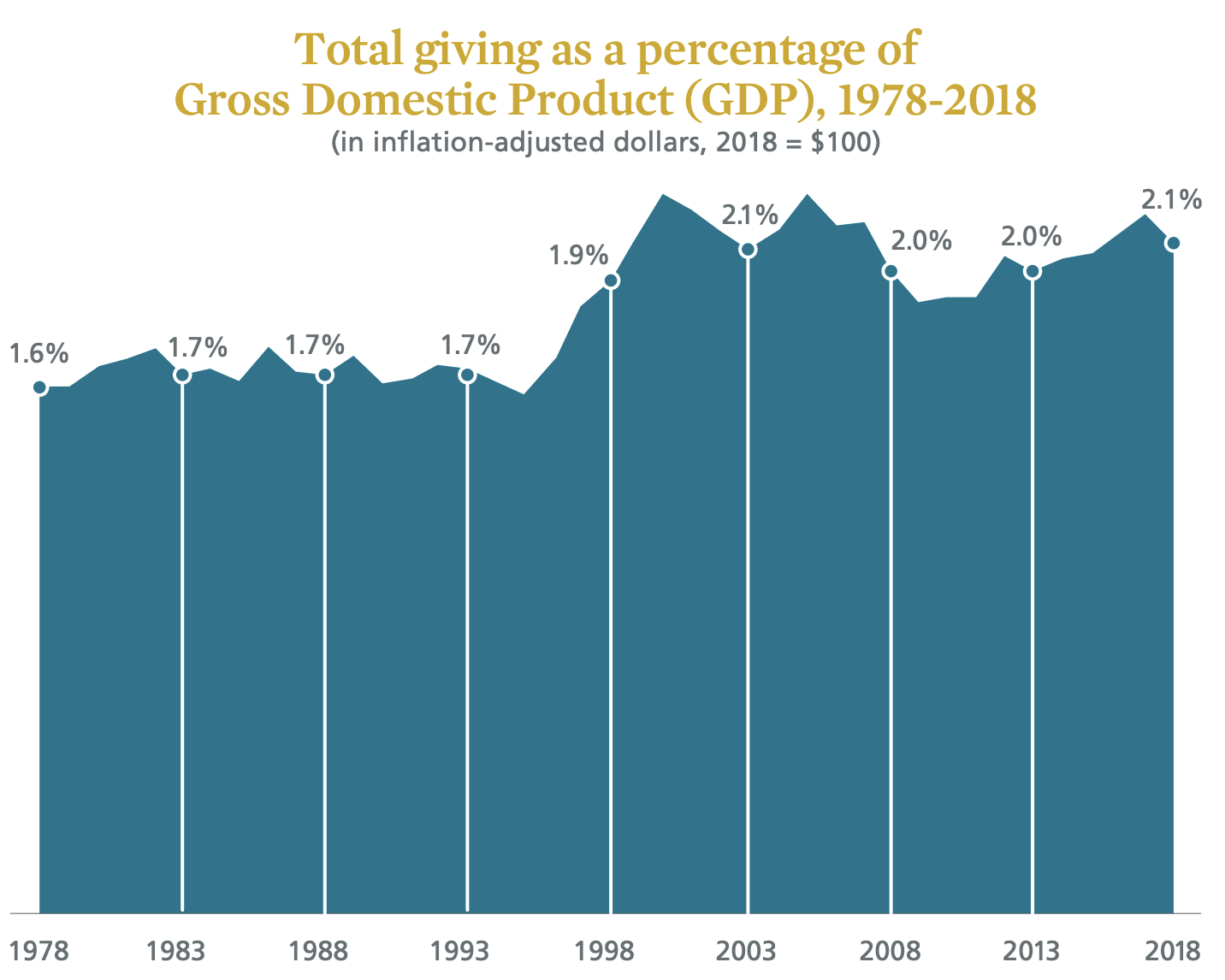

while remaining relatively stable around 2% of GDP in this period:

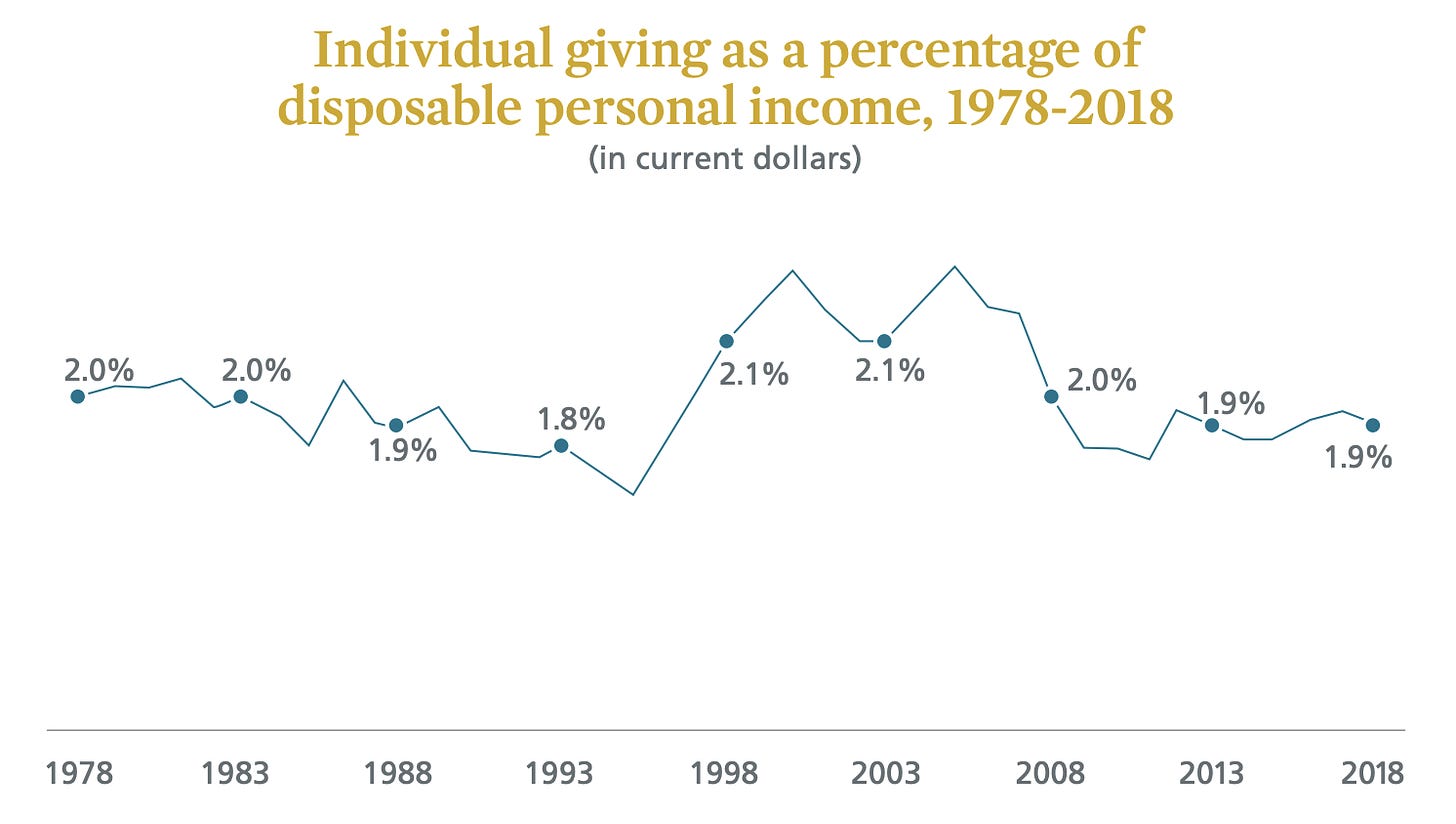

And this 2% stability also extends to the annual charitable giving of individual income:

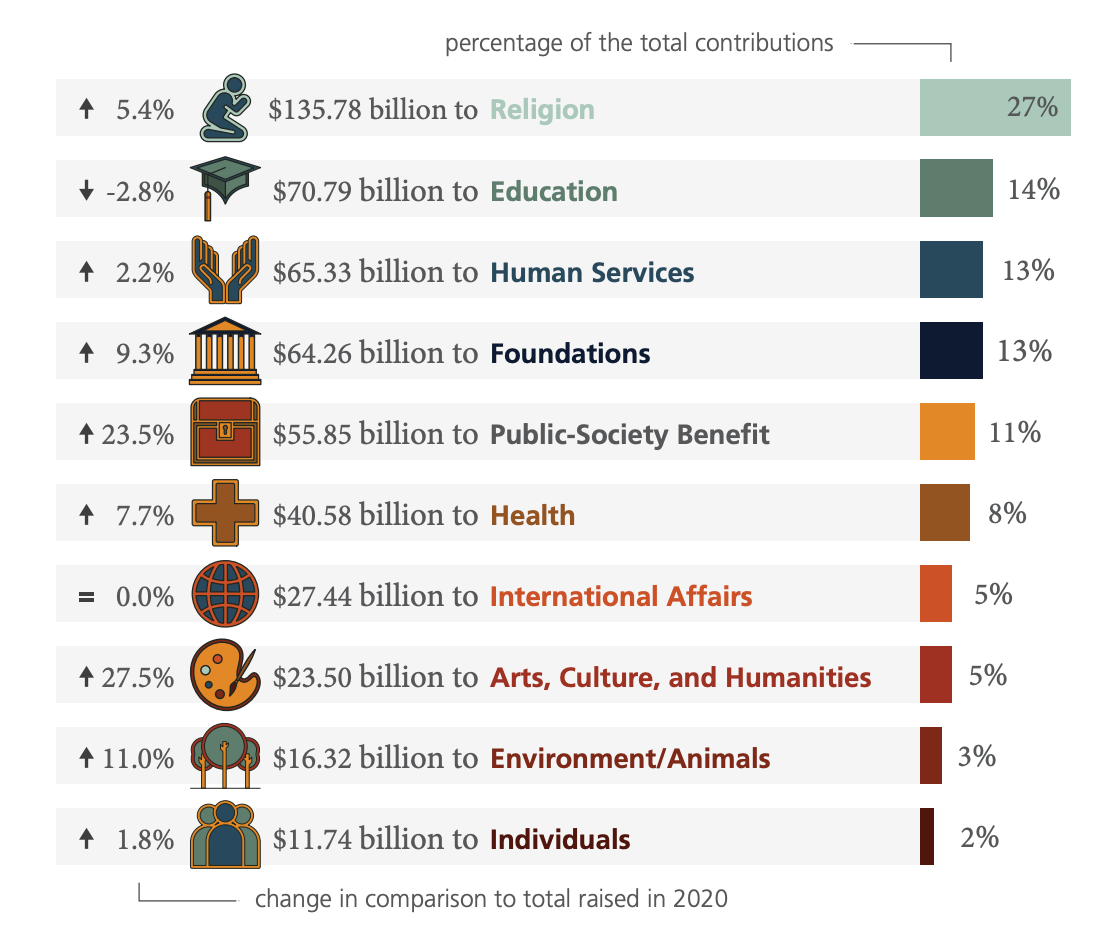

This giving is quite diversified across different cause types:

If we’re viewing this as an opportunity for a new business, only a portion of this massive market is realistically “capturable” by a given platform. Let’s assume that the overall allocations presented here are equivalent at the individual level. We should remove the following for being outside the purview of 501(c)(3)-focused giving:

27% to religious organizations

2% to individuals (peer-to-peer)

We might also remove the 13% to foundations (for being slightly adjacent to our typical view of charitable giving), and if we’re trying to be as conservative as possible, let’s apply a 20% discount to all remaining giving that, for whatever reason, is not appropriate for a giving app.

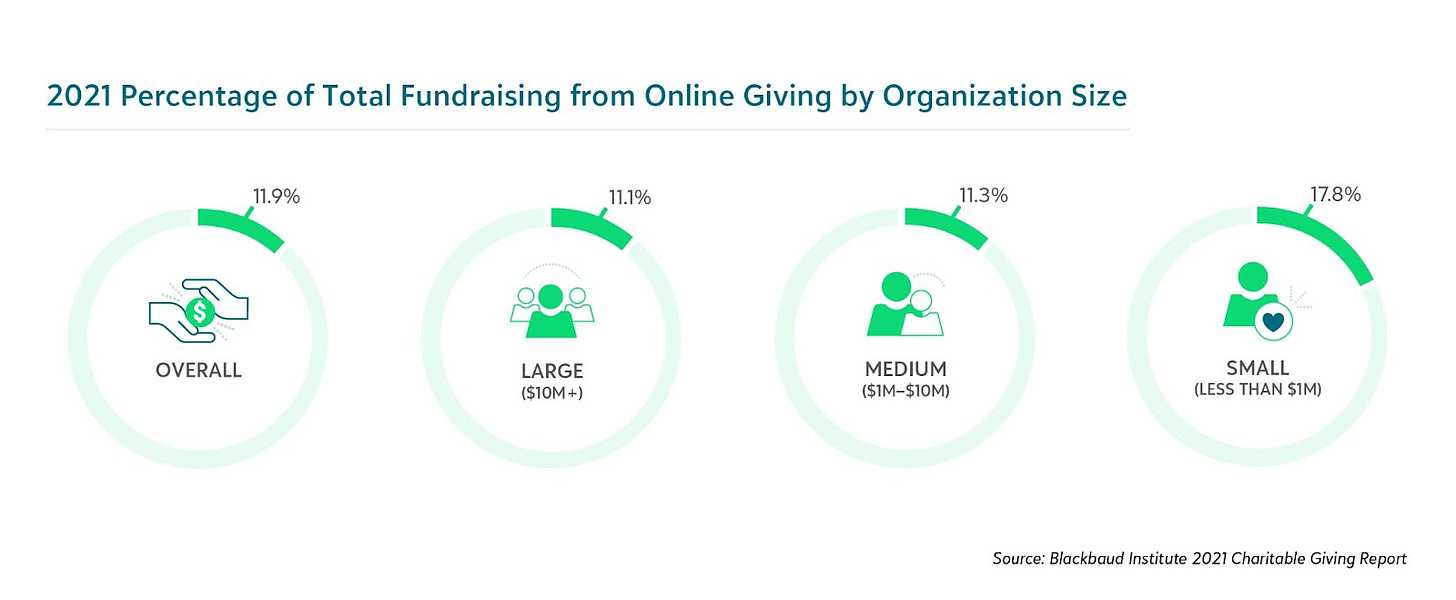

Even after all of these deductions, we’re left with $152B in annualized individual charitable giving. Despite this scale, charitable giving remains a fragmented, analog marketplace. Across the 1.8M registered 501(c)(3) organizations in the US, 80-90% are still transacted offline:

It’s not too surprising that smaller nonprofits would show higher online volumes given that the larger nonprofits are much more heavily dependent on large singular donations that necessarily occur offline. Note that this is not equivalent to the rate for INDIVIDUAL giving, but as our hypothetical target audience represents two-thirds of giving, I think it’s reasonable to say that these values are directionally aligned with individual giving rates.

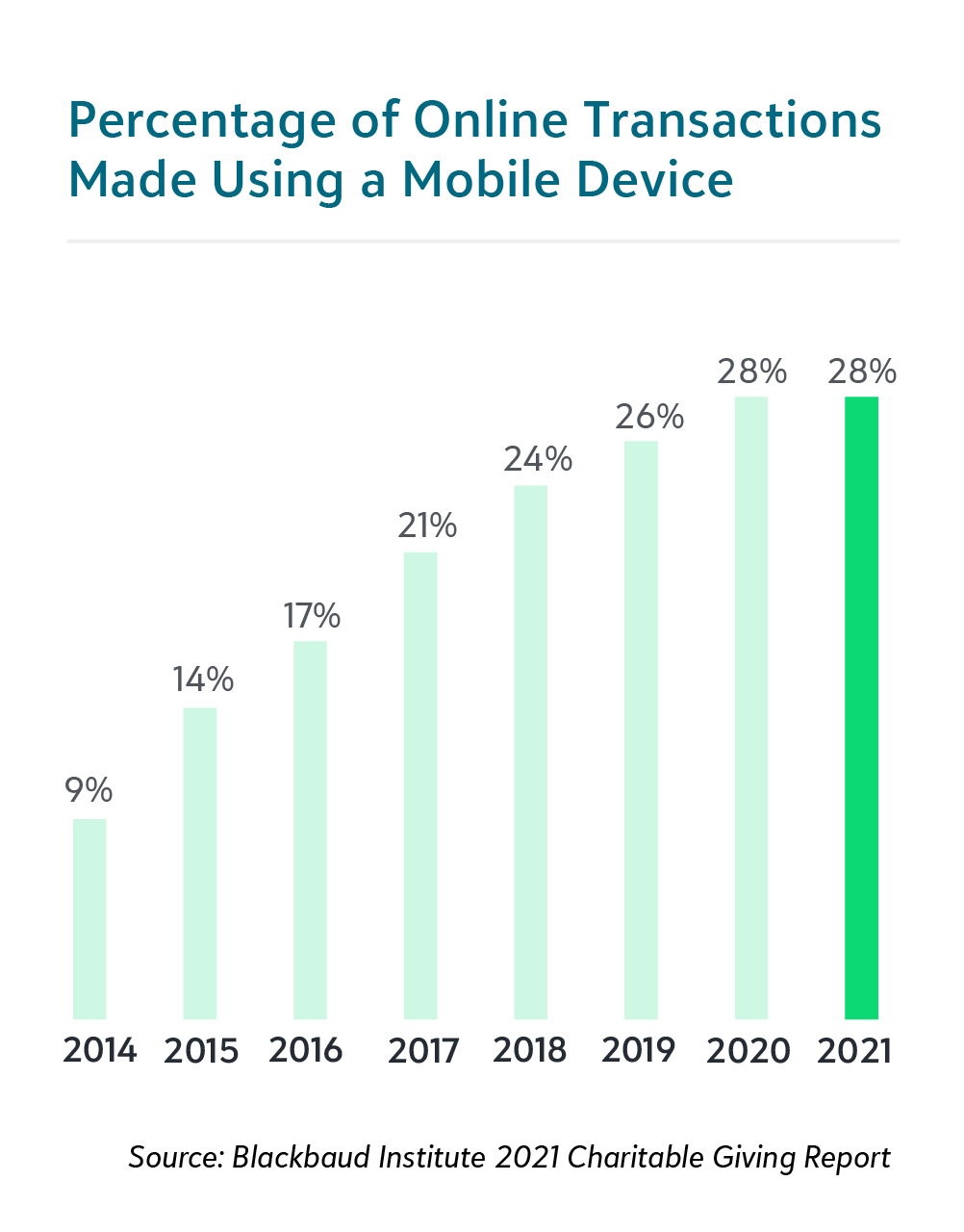

Of these online transactions, a minority are conducted on mobile:

This of course means that mobile penetration of charitable giving is somewhere in the 2-4% range. If we then adjust the prior TAM value, we come to:

Online donations are somewhere in the $15-$30B range.

Mobile donations are in the $5-$10B range.

Where are the apps?

Such conditions are precisely what most entrepreneurs and investors typically salivate over, so why is there still no dominant centralized digital marketplace for charitable giving?

The most obvious answer is stigma. It is uncouth, unconscionable, reprehensible, and downright evil to profit off of charitable giving. There are also the regulatory concerns. Professional fundraising is an onerous regulatory endeavor, with more than 40 states requiring annual filings and requirements changing constantly. Onerous, perhaps, but far from insurmountable. We built the necessary infrastructure at Omaze, and there is nothing proprietary in the setup - just diligence and perpetual staffing.

There’s a further app store concern, as there are with so many digital businesses these days. Both Apple and Google technically allow donations to flow through their IAP pipes but with very strict conditions. The reality for now is that, like Spotify, Netflix, and so many others (including GoFundMe), any charity marketplace app will require transactions to transpire outside of the app - harmful but necessary friction for donors.

None of these hurdles, either individually or collectively, feels sufficient to justify the lack of a GoFundMe-sized company focused on charitable giving rather than P2P fundraising. Regardless, the opportunity is there.

Donor Decline

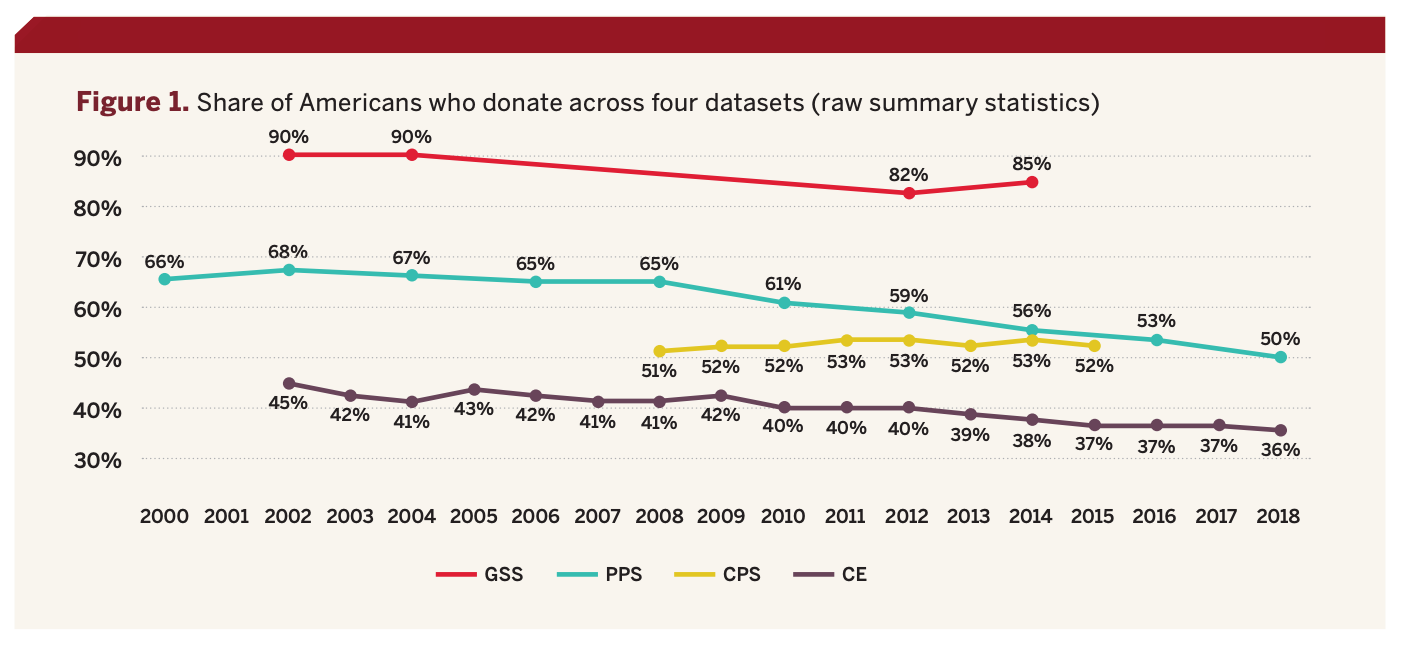

If this were purely a capitalistic endeavor, I would understand the ire, but there are very real problems faced by most nonprofits that are not being solved by the market today. Despite donation value largely remaining constant, the total number of donors has fallen precipitously over the past decade:

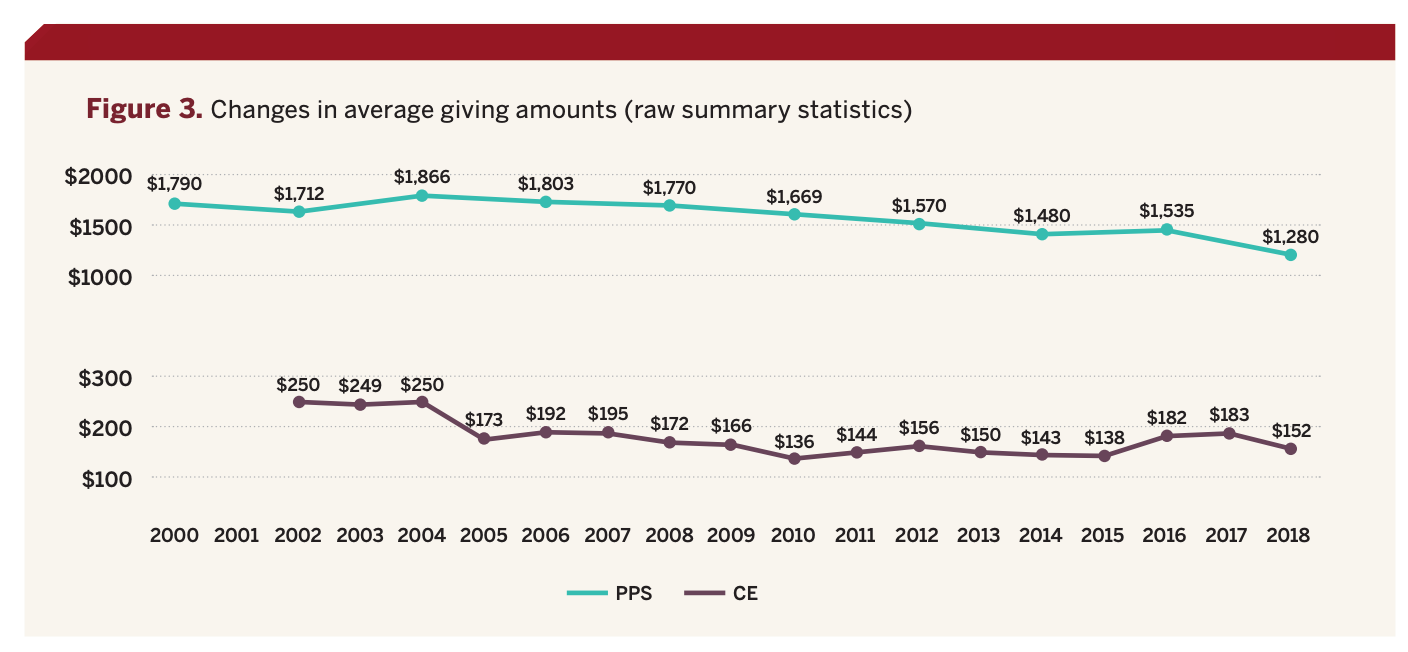

Charitable giving has been declining, especially since the Great Recession. The PPS study here is most robust and the one I’ll be using for further commentary. We see not only a fall in charitable giving from two-thirds of all households to just half, but that the total donation amounts have also fallen off precipitously:

So in the span of just a couple decades, we have 20M fewer Americans donating each year, and donating 30% less. Note that this flies a bit counter to the previously presented data showing total donations from individuals growing over the last 40 years. I suspect that this is to the significant data challenges I’ve found in the nonprofit space.

Cash Flows are Challenged

And even at current donation levels, nonprofits are consistently cash-starved. From FastCompany:

“81% of nonprofit leaders say access to capital is their biggest challenge, [and] most organizations don’t engage in fundraising experimentation because they’re worried about the perception that it might create.”

Even when they do hit fundraising goals, usage of these funds is highly restricted, since “only 20% of nonprofit funding in the United States is unrestricted. Most nonprofits gain grants that dictate they put money directly toward existing programs. Groups that can’t invest in basic management and support costs generally have trouble sustaining their impact.”

Restricted donations are an efficiency problem — it is an imposition by ignorant donors dictating the best ways to utilize funds. Rather than focusing on “total value created”, donors instead focus on the far more self-serving “make sure every one of my dollars is directed toward the end recipient”, even if that limits total impact:

“Part of the problem is that many funders have become obsessed with measuring their impact on a per-dollar basis, which means they’re more eager to give to specific projects than the institutional upkeep that supports them.”

This has previously been articulated as the “Overhead Myth”: “the mistaken belief that groups keeping operational or indirect organizational costs low are somehow more effective at accomplishing their missions”. Many nonprofits cap their “overhead” at just 15% because of the external narrative, NOT because this value represents the actual investment they require to carry out the mission.

“Ford Foundation President Darren Walker is among the most outspoken funders calling for a new grantmaking approach. “All of us in the nonprofit ecosystem are party to a charade with terrible consequences—what we might call the ‘overhead fiction”.

Instead of this “overhead minimization” framework, Walker and others have proposed a Pay What It Takes philosophy, “a flexible approach grounded in real costs that would replace the rigid 15 percent cap on overhead reimbursement followed by most major foundations”. This article also addresses how to better quantify and qualify “overhead” or “indirect costs”, split into four overall buckets:

Admin Costs: Costs of shared functions housed in headquarters, including leadership, finance, human resources, technology, legal, and bids and proposals.

Network & Field. Costs for maintaining field and network operations outside of headquarters.

Physical Assets: Costs of acquiring and maintaining project-related equipment, such as lab equipment and facilities.

Knowledge Management: costs for building and maintaining subject and program expertise and internal knowledge, including staff costs.

Let’s take nonprofits in New York City as a specific example of the challenge here. From this analysis, NYC nonprofits had total revenues of about $15B as of 2015, and yet on average, these nonprofits had just three months of cash on hand and operating reserves to actually remain solvent. Broadening out, we get a clear picture of a sector on the persistent precipice of disaster:

10% are insolvent

40% have virtually no cash reserves

40% have lost money over the last three years.

“At best, 20-40% of organizations appear to be financially strong, defined as having more than six months of unrestricted net assets.”

Note that “healthy” here uses just a 6-month cushion, where the standard rule of thumb in startup land, which knows a thing about burning cash, is maintaining ~18 months runway. And as such, the median nonprofit in NYC exists with an operating margin of 0%.

Growth is Difficult

Given that most nonprofits are cash-poor, it should come as no surprise that growth is difficult for all, and mega growth is near impossible. As of 2007, the Top 10 largest nonprofits were on average founded in 1903, and only 144 nonprofits have gone from founding to at least $50 million in revenue since 1970. Further, just 6 of these relied primarily on individual donors; the remaining 96% grew through mega donations from foundations or billionaires.

Let’s actually invert this. 90% of these “modern” $50M nonprofits relied on a single source of funding that accounted for more than 90% of their total funds available. Their scale came from extreme concentration, and any changes to the relationship with that single donor would result in decimation.

Of the aforementioned 1.8M 501(c)(3) organizations in the US, 76% have annual revenues under $100k, and just 3% have annual revenues greater than $5M. With such low annual revenues, coupled with low operational investment, it’s little wonder that only about one third of nonprofits actively invest in digital advertising, let alone additional B2C mainstays of active donor engagement and retention. I count no less than 30 current companies offering SaaS tools to nonprofits, but such platforms are unhelpful without both capital and personnel.

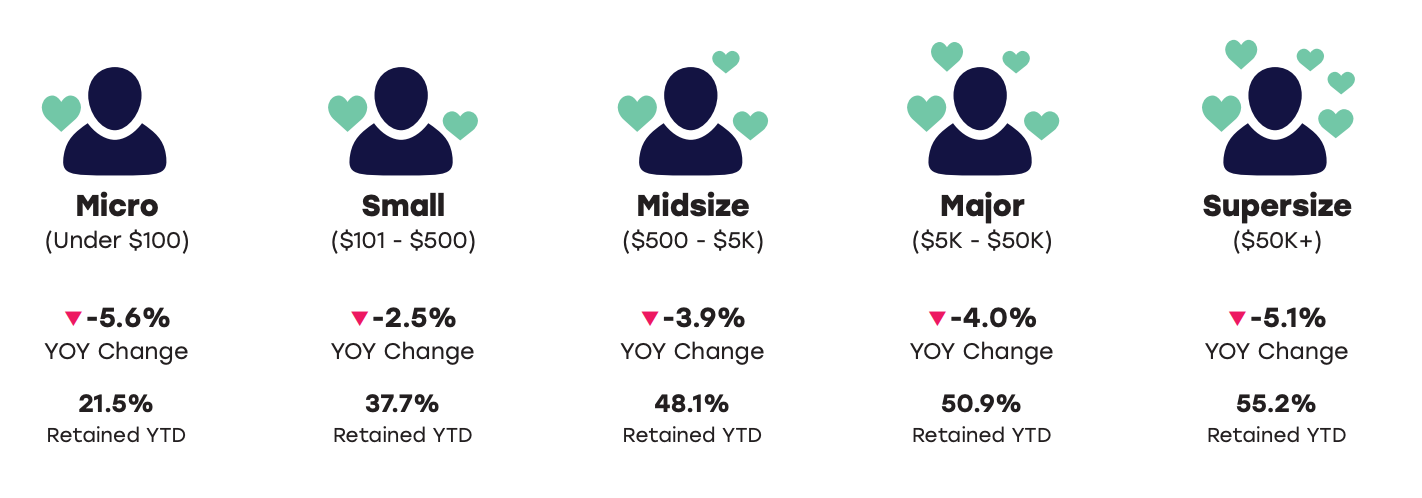

Annual retention of donors for the sector as a whole is under 50% (except for mega-donors):

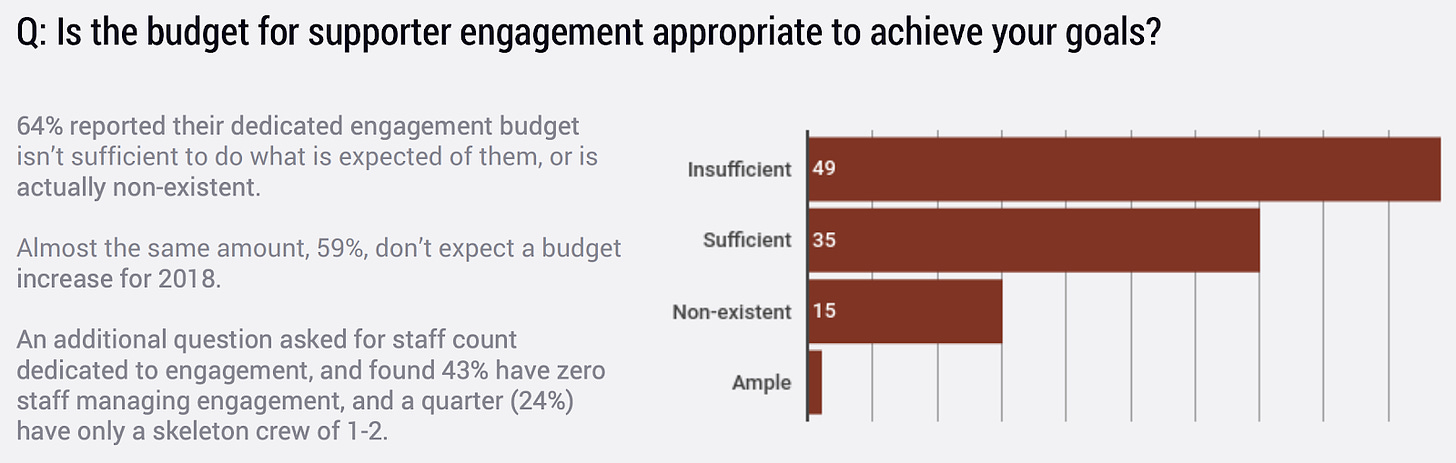

The unfortunate truth today is that nonprofits have almost no resources focused on engagement with their community. There is no budget:

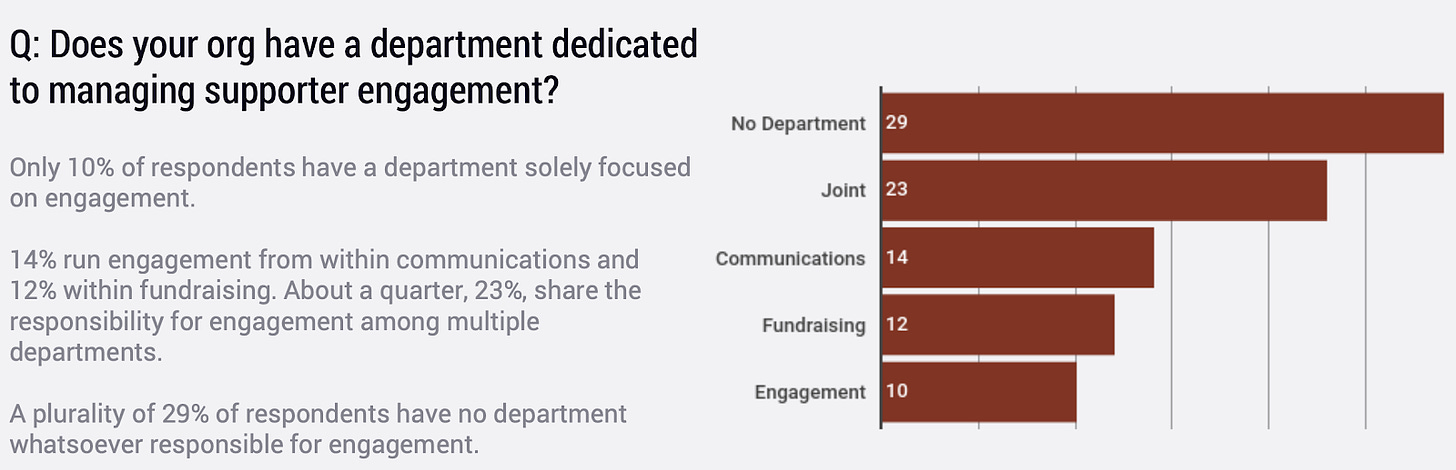

And without a budget, there’s rarely a team focused on regular engagement:

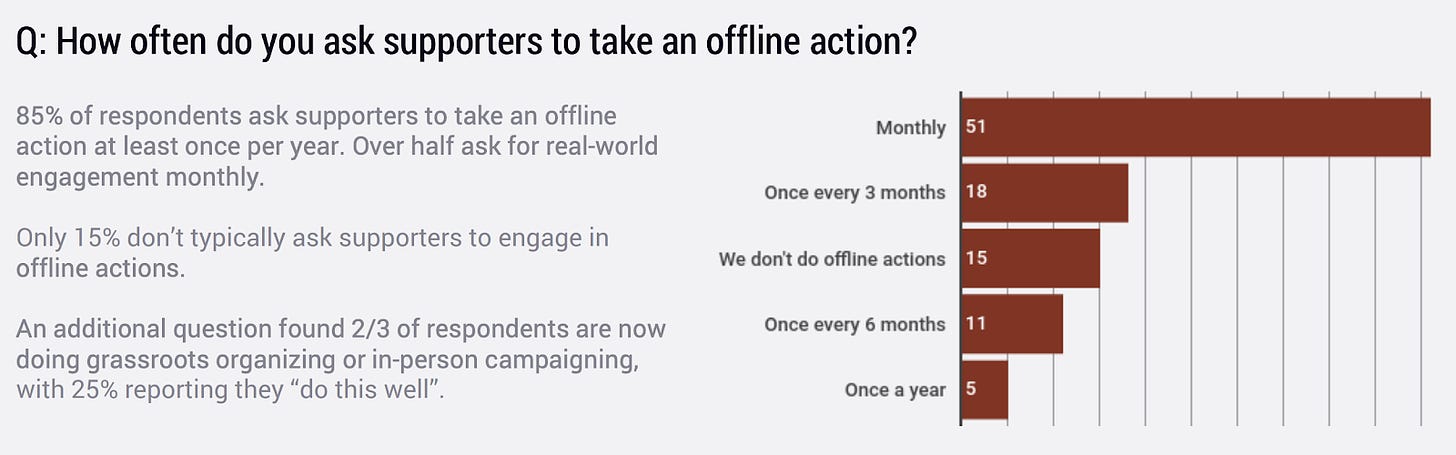

And without this team focused on consistent and persistent engagement, the offline actions that are necessary for the nonprofit’s optimal functioning are discussed at an incredibly infrequent cadence:

Great technology can’t fully replace humans in this donor feedback loop - at least not yet - but it can certainly make it easier for the understaffed to improve their baseline behaviors.

The Solution

It’s time to put aside the stigma and build the most obvious app possible - one that captures all of our annual charitable giving in a modern, frictionless form factor, and that can grow to incorporate additional donor behaviors as it scales.